Memories:

Lola grew up in a small town going to an all-girls catholic school. One time, she and her friends skipped school and grabbed a taxi to go to the mall. The driver ended up calling the school to let them know where their students had gone off to for the day. I’m not sure if it was from this offense, or from another, but she told me she once (or maybe more than once) had to kneel on rice grains for some time as punishment.

She told me another story from her college years. The greatest hits of the 50s-60s playing on the speakers during a dance social night. Ladies stood on one side of the gymnasium and guys grouped together on the other, scanning which of the girls they’d be brave enough to approach for a dance. It was in this same scenario that my Lolo picked her out of the crowd.

I spent my childhood afternoons after school doing homework in Lola’s living room in front of the TV playing Phineas & Ferb and eating Velveeta Mac’n’cheese with Spam. For special occasions, she’d bring the pans of pancit, lumpia, and beef skewers.

Lola loves fashion. We would walk around Dillards and Macy’s at the mall where she’d study the stitching and patterns. If I said I liked something, she’d respond, “I can make that.”

In her room lives a large sewing table where she made alterations to my 8th grade dance dress and pants that were made for girls taller than 4’10”. She set aside my own pair of house slippers with a mesh toe box and floral patterned beads for when I’d visit. While browsing through Urban Outfitters in high school years later, I came across those same slippers for $35. Lola laughs and leans in, “I bought you those slippers for $3 at the market.”

When Lola came over to our house on the weekends, she’d always walk out to the lone banana tree set beside a stream in our backyard. She loves watching over plants and gardens.

I knew we’d be going to the Philippines.

I grew up hearing stories of my grandparents’ time here. Tita told me her experience visiting for the first time in the 2010s.

“When you go, it’ll make sense. It’s important to see where you came from.”

Those words remained in the forefront of my mind as our time in Chiang Mai drew to its end and closer to our arrival in Manila.

“Manila is too crowded,” Lola would say with a shake of her head. So I expected that it would possibly feel like New York City. I like NYC. I could like Manila if that was the case.

“We will try to meet you out there,” they said when I gave them the tentative dates. It wouldn’t happen for varying reasons, which I had to anticipate given the extent of travel we experienced. Over twenty hours on and off planes, navigating airports, and pushing bags through security points is no easy feat.

I had not given myself time to consider my expectations for my arrival in the PH before the flight.

“3 hours is plenty to write through this process.”

So I delayed the process, and the emotions that I knew would surface. I did not know why I was procrastinating on it at the time. I’d later realize that I was avoiding the feelings of “otherness” and “not belonging” I carried, predominantly through my childhood and teen years, regarding my identity; where I came from and how that shapes who I am.

“You are not Filipino. You are Filipino-American.”

That’s the biggest point. I knew there existed a distinction, but I couldn’t quite articulate it until we arrived.

Being a half-Filipino, half-Puerto Rican, raised in America, I was led to believe it was a shame I grew up so removed from my grandparents’ mainlands. I had the impression that being a “hybrid” was that I belonged to a “lesser than, uncultured” group (which is untrue, but I think a lot of people in my position feel this way whether or not they’ve been able to say it out loud), and it influenced my demeanor the first week of arriving here.

I’ll get to worthiness and culture-acceptance later, but my most immediate dilemma upon interacting with everyone here was that I didn’t know how I should behave. Should I try to be “as Filipino as possible” or claim I’m half-Filipino?

No way. I thought. That would just set me up for failure. I don’t know any Tagalog and was raised on only a handful of meals exclusive to holidays and birthdays. I’d rather not be judged for my childhood or for not yet learning the language. Anyways, I can get away with skipping that conversation since I’ve been told enough that I don’t even look Filipino.

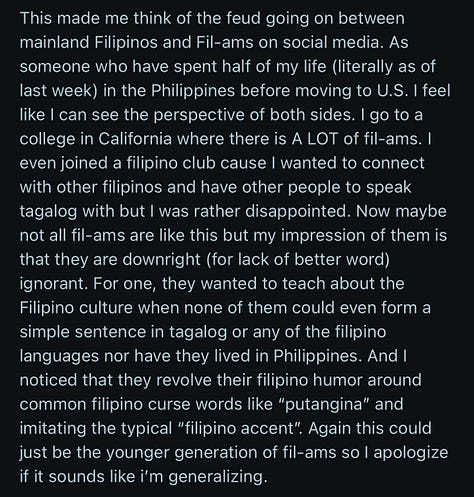

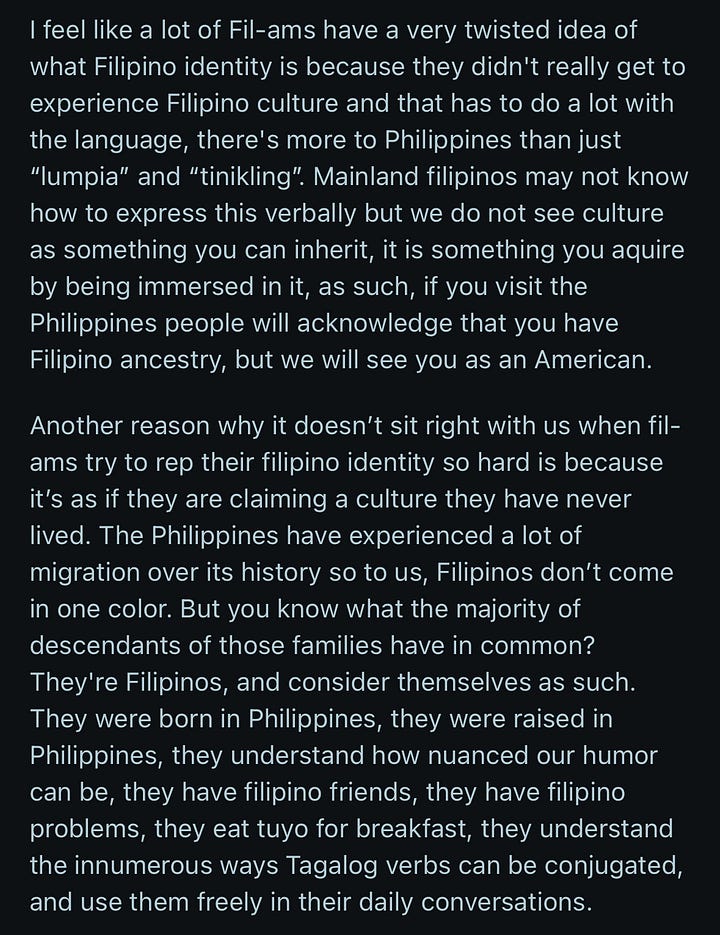

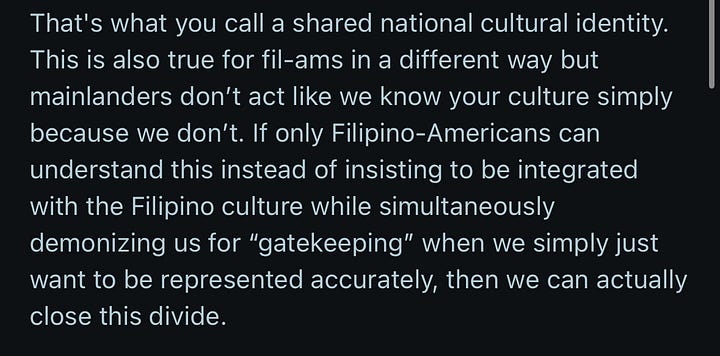

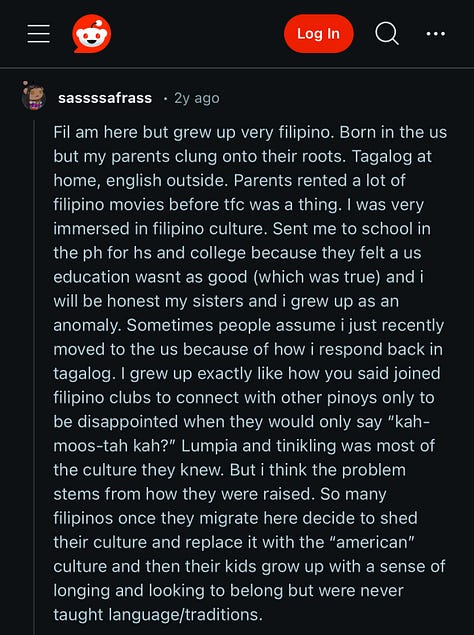

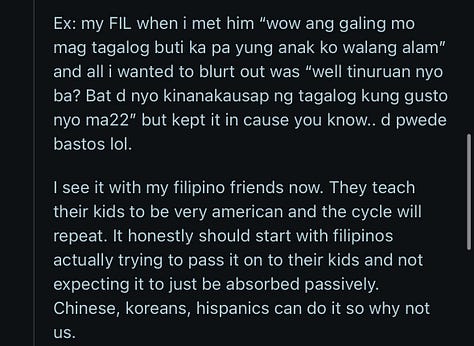

People like me claiming ownership of the culture is a point of discussion that many Filipinos wish Fil-Ams would understand. According to this Reddit, at least:

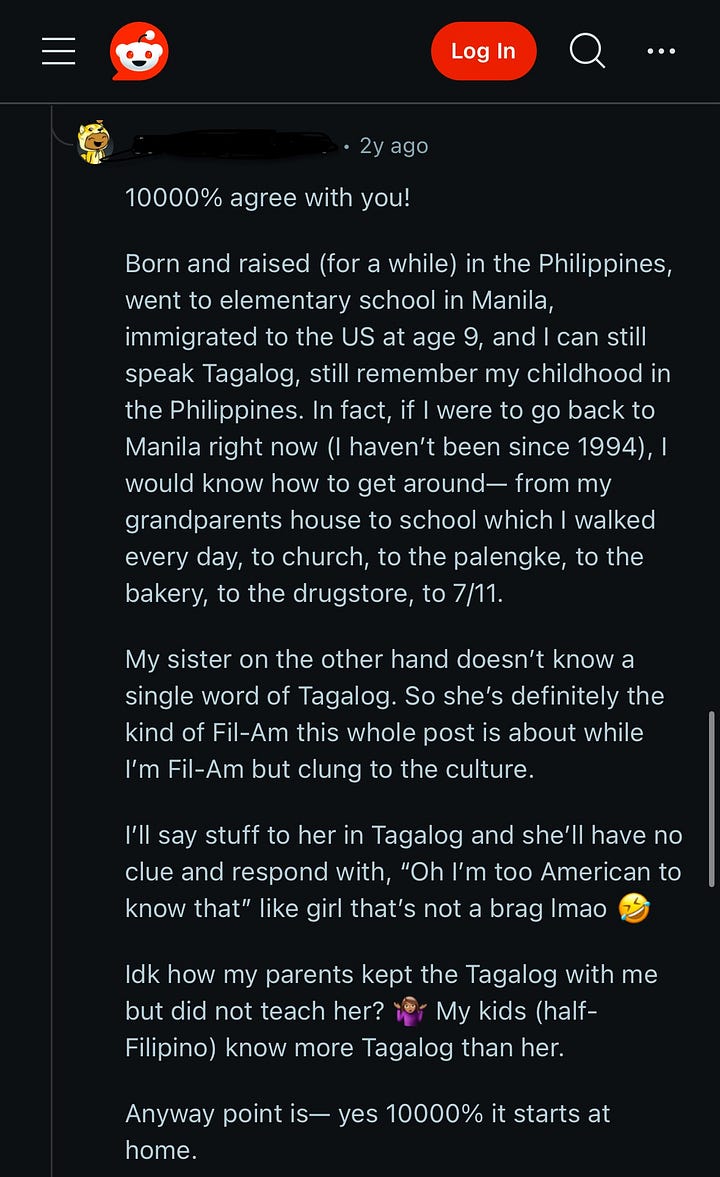

And the Fil-Am response:

When we arrived, I was afraid I’d be judged for not being “Filipino enough”.

I thought that’s why everywhere we went, I’d get stared down. The truth is that no one expects or wants me to pretend that I have had a more immersed childhood than I had.

Knowing my own experience and culture, and not trying to fit it into the mold of another, is the only thing I can do. Being kind, respectful, and open to new experiences is all I can bring to this experience. We are spending more time in here compared to a lot of American-born Filipinos. I will experience the culture in micro-doses. Just like any other country, the experience, languages, dialects, and lifestyles vary according to location. I know that even by walking around and meeting new people, I am still seeing a version of this country that’s different from those who live here because I am a foreigner. Which brings me to the next significant point:

That’s okay.

It’s okay that I will never know Filipino culture like those who were born and raised here. It’s okay that I cannot inherit this culture, because I was immersed in the American culture. And that’s okay, too.

It’s okay that my childhood looked, felt, and unfolded the way it did. It is not a shame that I grew up where I did. It is not a shame that the Filipino culture I was exposed to offered me enough experiences to find some association with the country, even if it’s considered “not good enough” to some people.

I am not upset. I’m not lost. I know who I am. I accept my story. I am not ashamed of what I didn’t experience. I am not ashamed of what I was given. I love my family. I am grateful for their sacrifices. I am grateful for my life and the opportunities I’ve had—because of where I was born and raised, and especially because of the people who made a way for me.

Shame.

Actions motivated by it didn’t make me feel brave or confident. It made my shoulders curve forward and my voice dialed to a frightened whisper; practically screaming, “I’m unsure of myself! I’m terrified!”

I was a classic form of entertainment for those who enjoy using insecure people to inflate their egos. On the level of safety in new environments, this is not what I’m trying to put out. The only way to feel safe while we travel is to rid myself of anything that signals weakness.

Shame makes me weak.

If I am to tackle this weakness, it means facing the deep-rooted shame for being an American-born.

“Lesser than”

Having spent a long time working through and overcoming feelings of shame on a personal-psychology level, I have the capacity to work through it on a cultural-belonging level.

Here are the methods and beliefs I’ve come to so far:

Remove measurements of validity and worth.

My experience is valid. I am worthy of a life of joy, confidence, and peace, regardless of culture. Period.

Tell the story by what happened, not by what it means.

If there’s a personal experience that aligns with a cultural experience, then it can be a subject I explore and educate myself further on.

If the only cultural ties I have are the food, stories, and grandparents, then that is what I have. Could I look my family in the eye and claim having those is not good enough? Never.

Show gratitude by saying “I love you” and “Thank you,” and by asking questions.

Proving gratitude through expressing shame and self-loathing is a task given by those who have not done the work of understanding their own experiences and made peace with their own differences. Gratitude amplifies the beauty of what exists, while shame amplifies the emptiness of what is lacking.

We are all belonging to a culture.

We all lack education of the cultures apart from our own. No one is wholly informed and highly attuned to the nuances of every culture. I can barely say so for the culture I do belong to.What people of one culture ultimately want is for those visiting or addressing them to be respectful, humble, kind, and curious. That’s all anyone can be when learning something new, and the only way to create an environment conducive to new friendships and richer experiences.

Culture is a facet of my identity, it is not the whole.

It is important because it is relevant to how I behave and see the world. I am also made up of my unique experiences, interests, skillsets, talents, relationships, neurological processes, mannerisms, dreams, etc. There are intersections that can be attributed to culture. Like the values and beliefs we’ve inherited, we will either live following them without conviction to update anything, or we’ll wonder what it’d be like to make adjustments. The American culture says there’s nothing wrong in questioning these things. It encourages individualistic thought and says it’s okay to break away or to remain distant if that’s what I want. I can see the validity in the arguments for and against this. There’s no denying that I fall most in line with the individualistic thought because it feels like an expression of free will. It feels like when I am drawn to collectivistic belonging, it is from innate desire for it. Maybe that’ll make people roll their eyes (“So American”), and maybe it’ll get some head nods. I know I’m young and I believe everyone’s allowed to change their minds. I believe there’s truth in every argument. I’m not trying to be correct by writing this. I am simply living.